Basic Chord Theory

It's Simpler than You ThinkWhat ‘Basic Chord Theory’ Will Cover

- The Major Scale – The Diving Board into the Pool of Chord Theory

- Chord Families – What chords are played in what keys?

- What is a G#maj9(b the 3rd)? – Chord Formulas

- What am I playing on the Guitar?

- Slash Chords

- Key Note Signatures

For a PDF outline of some of the material in this section, click here: Chord Theory Outline.

Click for PDF

For a PDF outline of some of the material presented here, click the button.

The Major Scale

The Diving Board

I like to think of the major scale as the ‘diving board into the pool of chord theory’. So much information can be drawn from a major scale:

I like to think of the major scale as the ‘diving board into the pool of chord theory’. So much information can be drawn from a major scale:

- key note signatures (of less importance to guitar players)

- chord families – which chords belong in the key of the scale

- the chord formulas for chord variations

What is a Major Scale?

A major scale is made up of 8 notes. The notes when played in sequence sound like “DO RE MI FA SO LA TI DO”. The key of C is built off the C major scale, the key of G is built from the G major scale, etc. The notes of the C major scale are: C – D – E – F – G – A – B – C (notice there are no sharps or flats in the key of C).

We can number each of these notes 1 through 8.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

C D E F G A B C

An important observation to make here is the interval (or spacing) between each numbered note. I’ll use “w” to represent a whole step, and “h” to represent a half step. So the interval between the numbered notes in the major scale could be represented like this:

1 w 2 w 3 h 4 w 5 w 6 w 7 h 8

Or you could say there are whole steps between all of the notes except between 3 & 4, and 7 & 8. If we follow this pattern, we can “build” the major scale in any key. Look at the following chart:

A Major Scale Chart

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

G A B C D E F# G D E F# G A B C# D A B C# D E F# G# A E F# G# A B C# D# E F G A Bb C D E F

There are a couple of important things to note in the chart above. In each key, between notes 3 & 4 and 7 & 8 there are half steps. Between all the other numbered notes, there are whole steps. Also, note that each letter A through G are represented in each scale. In the key of G we don’t go from E to Gb because we would skip “F”. Likewise, in the key of F, we don’t go from A to A# because we would not be notating B anywhere in the scale. Also, notes 1 and 8 are always the same, only an “octave” apart in pitch.

For a complete list of the major scales in PDF format, click here: Major Scale Sheet.

Click for PDF

Chord Families

How Chords Work Together

Of more relevance to the guitar player are Chord Families, or what chords go together in the different keys. Looking again at the C major scale, with the numbered notes we have:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

C D E F G A B C

Each note can represent a specific chord in the key of C. For instance, the first note ‘C’ represents the first chord C (major). The fourth note ‘F’ represents the fourth chord F (major). Some of the numbered notes represent major chords, some minor, but the seventh represents a ‘diminished’ chord. Look at this chart of Chords for the Key of C:

I ii iii IV V vi vii(dim)

C Dm Em F G Am Bdim

Notice that for chords, we typically switch our numbers to Roman Numerals: uppercase for major chords, lower case for minor chords. So we see that the major chords in the key of C are chords (I, IV and V): C, F, and G. The minor chords (ii, iii, and vi) are: Dm, Em, and Am. From this point on I will omit the seventh chord, the diminished chord. I call this the C Chord Family.

For the key of G (and any other key) we can apply the same approach to find our major and minor chords:

I ii iii IV V vi vii(dim)

G Am Bm C D Em F#dim

Thus the G Chord Family comprises these major chords (I, IV and V): G, C, and D. And these minor chords (ii, iii, and vi): Am, Bm, and Em. For a full chart of these Chord Families, click here: Chord Families. Look at the graphics below that show common chord families that beginning guitarists use (click to enlarge – or click the link below for a pdf version of this chart).

Click here to download a PDF version of the above diagram: Chord Family Diagrams

Nashville Number System

One important note to make here is the Nashville Number System. The Nashville Number System does away with Roman Numerals and uses regular numbers to represent chords. This makes it easy when chording a song according to the numbers rather than to a specific key, which is sometimes useful if you know the song may be transposed in the future.

In the key of G a 1-5-6-4 progression would be G-D-Em-C. We know that the 6 chord is minor. If, however a minor chord is instead to be played as a major we can notate it with a capital ‘M’ besides.

Chord Families PDF

Chord Chart PDF

Chord Formulas

What Makes a Chord?

Chord formulas refer to the actual notes being played in a chord and associates the numbers (1 through 8 ) of the major scale to those notes. Actually sometimes we repeat the scale an octave higher and continue counting up to number 13.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13... C D E F G A B C D E F G A...

Major Chords. For example, the C major chord is comprised of the notes C, E and G. When we look at the C major scale, we notice that these are notes numbered 1, 3, and 5. We then can deduce that the ‘chord formula’ of the major chord is 1,3,5. If we want to know the notes of any major chord, we can jump to that chord’s major scale and find notes 1,3,5 and know which notes we are playing. Thus the G chord is played by notes G, B, D. The D chord is comprised of notes D, F#, A. Etc.

Minor Chords. A minor chord takes the the 3rd note of the major chord and “flats” it, or lowers it a half step. It’s chord formula is 1,♭3,5. We can look at the C scale, and take the notes C, E♭, and G. ‘E’ is the 3rd note which gets “flatted”, and becomes an ‘E♭’ to make the Cm chord. The Dm is comprised of notes D,F,A.

Other Chord Variations. Sometimes we see chords like C2, Csus, C6, C7, Cm7, Cmaj7, Cmaj9, Cadd9, etc. These notations refer to special ways of handling the numbered notes of the chord’s major scale. Look at the following chart:

Chord Name Formula Notes Diagram

C2, Csus2 1,2,5 C,D,G x3x033 Csus, Csus4 1,4,5 C,F,G x33011 C6 1,3,5,6 C,E,G,A x32210 Cmaj7 1,3,5,7 C,E,G,B x32000 C7 1,3,5,b7 C,E,G,Bb x32310 Cadd9 1,3,5,9 C,E,G,D x32033

Click here for a much broader chart on chord formulas.

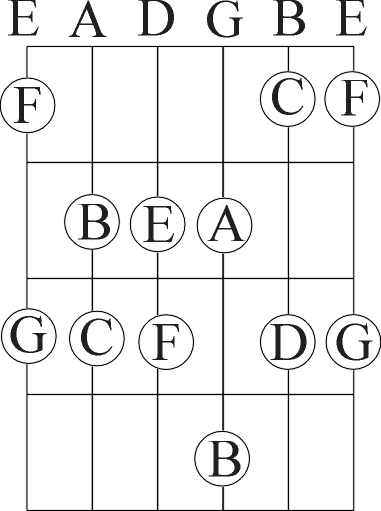

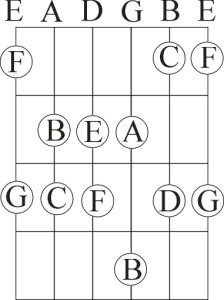

Look at the chart below to see the notes on the first four frets of the guitar. The sharped/flatted notes are left out to avoid clutter. But this chart can be used to modify the open chords you play, using the chord formulas in this section.

Click for PDF File

What Am I Playing on the Guitar

Strings and Frets

It might be helpful to look again at the graphic.

A couple of observations from the above graphic include:

- The string names E, A, D, G, B, E. These strings in this order are named from lowest pitch to highest pitch. We also refer to the strings by numbers. However, we start with the “top-pitched” note, thus the high E is number 1, the B is number 2, etc. Sometimes we see them written this way: E1, B2, G3, D4, A5, E6. We call E1 the “top” string, and E6 the “bottom” string.

- Each fret represents a half-step interval. When E6 is fretted on the 1st fret, the note played is a half-step up from E: the F note. The note played on E6 on the 3rd fret is G. The note played on B2 on the 3rd fret is D. This is especially important when we incorporate chord formulas to modify an existing chord.

Applying Chord Formulas

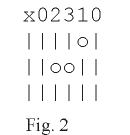

Once you know the strings and the half-step intervals of frets, you can begin to apply chord formulas to standard chords. When you see the chord G2, you can take your normal G chord and modify it. The G chord is G,B,D (according to the formula 1,3,5). The G2 uses the chord formula: 1,2,5. There is no 3rd note, so we drop the 3rd note (B) of the G chord and include the 2nd note (A). Thus we need G,A,D.

Let’s look at a typical G chord:

I’ve included the notes being played by each string. We could open the A5 string to drop the B and gain an A note. However, when modifying chords we generally do not want to add our ‘new’ note on either of the the lower two strings. So we will mute the A5 string to drop the ‘B’ and we will move our ‘1’ finger to the G3 string in the second fret. This will take that G note up a whole step to an A. Here is how the diagram would look:

There you have it. A perfect G2 chord! Following this procedure we can modify many of the chord shapes we already know. Sometimes, however, we may need to start from a different chord shape. At times barre chords can help us here. Other times, we may need to invent a whole new chord from scratch. Or we could just Google it, but what would be the challenge of that?

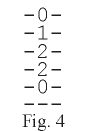

Types of Chord Charts

Figure 4 demonstrates how we would show the Am chord using tablature, or simply, TAB. The top line represents the top string, or E1. This chart says that E1 is played open, B2 is played on the first fret, G3 is played on the second fret, etc. There is no number on E6 meaning the string is not played. Because these numbers are ‘stacked’, we know they are played simultaneously (or strummed). For more information on how to read TAB, click here.

Slash Chords

What is a Slash Chord?

The term “slash chord” refers to a chords whose bass note (the lowest note played) changes from the root note to another note. These are examples of slash chords: G/B, D/F#, C/D, Bm/A. In the G/B chord, the bass note is a B note and can be played like this: x20033. The D/F# can be played as 200232 (using the thumb on the E6 string). The C/D would be xx0010. And the Bm/A can be played x04432 or substituted by a Bm7/A, 524232 (the pinkie reaches to the E6 string on the 5th fret).

Two Common Slash Chords

Probably the two most common slash chords are the -/2 chord and the -/3 chord. The -/2 is where a chord’s second note is played in the bass, such as F/G, G/A, A/B, C/D, etc. I play most of these as a slideable chord like this F/G: 3x321x. This shape can then be slid up the fretboard to create a number of -/2 chords. For the C/D, however, I use the pattern above: xx0010.

The ‘Slash 2’ (-/2) Chord

The -/2 chord is often built off of the IV chord (see Chord Families) and can be written as IV/2 and is substituted for the V or V7 chord in any given key. In other words, the IV chord in the key of C is F. The F/G can be substituted for the V or V7 chord (G or G7) in the key of C. A slideable version of this chord is:

| -/2 | Diagram |

| F/G | 3x321x |

| G/A | 5x543x |

| A/B | 7x765x |

Another ideal use for this chord is when modulating to a different key. If I am switching to the key of G from any other key, I use the IV chord with its 2nd note in the bass, or the C/D chord. If I’m switching to the key of C, I will use the F/G; for switching to D, I will use the G/A. There is another use of the -/2 chord built off of the bVII (“flatted seven”) chord. The bVII chord is the major chord that is a whole step lower than the I chord in any key. The bVII in the key of G is F, in the key of C it is Bb, in the key of D it is C and so on. The bVII/2 many times can be substituted for the I7. In other words, instead of playing the G7 in the key of G, the F/G can be played. Instead of the D7 in the key of D, the C/D can be played. Instead of the A7 in the key of A, the G/A can be played. And so on.

The ‘Slash’ (-/3) Chord

More popular than the -/2 chord is the -/3 chord. This chord is often used as a “transition” chord or “passing” chord from a major to its relative minor (or vice versa). The relative minor of G is Em (the vi chord in that key), of C is Am, of D is Bm, of A is F#m, etc. Many times we use a transition between these chords. This transition chord is the -/3 chord played against the V chord, or the V/3 chord. In the key of G the V/3 chord is D/F# and the vi chord is Em. Look at this chart:

| I | V/3 | vi |

| G | D/F# | Em |

| C | G/B | Am |

| D | A/C# | Bm |

| A | E/G# | F#m |

These -/3 chords can be diagrammed as follows:

| -/3 | Diagram |

| D/F# | 200232 |

| G/B | x20033 |

| A/C# | x42220 |

| E/G# | 476×00 |

Post a comment with any questions.

Key Note Signatures

How Many Sharps or Flats in a Key

Key note signatures refer to the number of sharps or flats in any key. For pianists and other musicians who largely rely on sheet music to play their instruments, it is common to refer to “The Circle of Fifths” to determine key note signatures. However, this can be cumbersome. And many guitarists don’t even refer to keys by their signature. Looking at the major scales one can easily determine the key note signatures by counting the numbers of flats or sharps in the scale. For instance, the key of C has no sharps or flats.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

C D E F G A B C G A B C D E F# G D E F# G A B C# D A B C# D E F# G# A E F# G# A B C# D# E F G A Bb C D E F

- The key of G = 1 # (one sharp)

- The key of D = 2 #

- The key of A = 3 #

- The key of F = 1 ♭ (one flat)

- etc.

i wanna know how e major is used in song “hotel california” as b minor chord didn’t consist e major chord.

Thanks Ashish for your question, and I apologize for the delay in responding. According to the sheet music this song is written in 2 sharps which is the key of D major or (B minor). The chords in this key are D, Em, F#m, G, A, Bm and C#dim. You are right, there is no E major, and no F# major for that matter. Basically, a song does not have to follow the “rules”; it can borrow chords from other keys, or change a minor chord to a major or vice versa. This adds more complexity and depth to a song, and is often a challenge for the song writer to break out of the musical box or constraints of a simple major or minor scale. Having said this, also, I have found many times that songs starting in minor keys tend to break these “rules” more often than in major keys. There are no hard and fast rules about what chords can or cannot be used, just the guidelines of the key the writer is in, and then his creativity and smoothness of adding more variety to it.

I dig your site. Very cool!! Hope to hear from you.

Thanks Jon! I appreciate your kind words.

David

I miss the old jam sessions. Please give me your email. Jon

thanks for creating a site like this